Indian agritech startups are only still scratching the surface and the lack of diverse business models is one indicator of how nascent the sector still is

Omnivore cofounder Mark Kahn says India needs to evolve beyond agritech to agrifood life sciences or AFLS, which is seeing a global revolution currently

Investors such as Omnivore believe that agritech startups have the opportunity to go for bumper IPOs because agribusinesses have been lapped up by retail investors

Even though India’s agritech ecosystem is the third largest in the world, agritech startups often fly under the radar in comparison to the startup ecosystem. Despite record-breaking funding in 2021 for ecommerce & D2C, fintech and enterprise tech startups, capital inflow for the agritech sector was rather sedate.

As per Inc42’s agritech ecosystem report, startups in this sector raised over $1.4 Bn through 189 funding deals between 2014 and December 2021. But in 2022, Waycool’s $117 Mn round signalled a turning of the tide, as it was the largest-ever funding round for any agritech startup in India.

The floodgates seemed to have opened since then. Arya.AG bagged $60 Mn at a $300 Mn valuation and as reported exclusively by Inc42, Dehaat is on the verge of entering the unicorn club. So is agritech becoming a mainstream sector in the Indian startup ecosystem in 2022?

For venture capital fund Omnivore, there was never any doubt that agritech would rise to prominence. Omnivore’s thesis is that India’s agrarian economy and the push to bring tech into agriculture would naturally unlock value chains that have long been left untapped.

“More people understand agriculture in India than any other sector. Agritech is a simple business in reality, but it’s very hard to execute because of the diversity of the addressable base,” the agritech-focussed VC firm’s cofounder Mark Kahn told Inc42 in a recent interaction.

Agritech Needs Diverse Business Models

India is home to more than 15.2 Cr farmers and agriculture contributed around 53.89% of India’s total gross value added (GVA) in 2021. However, the prevalence of traditional farming methods and middlemen in the value chain have pushed farmers to the very brink, leading to protests such as the ones that flared up in 2020 and 2021 around the farm reform laws.

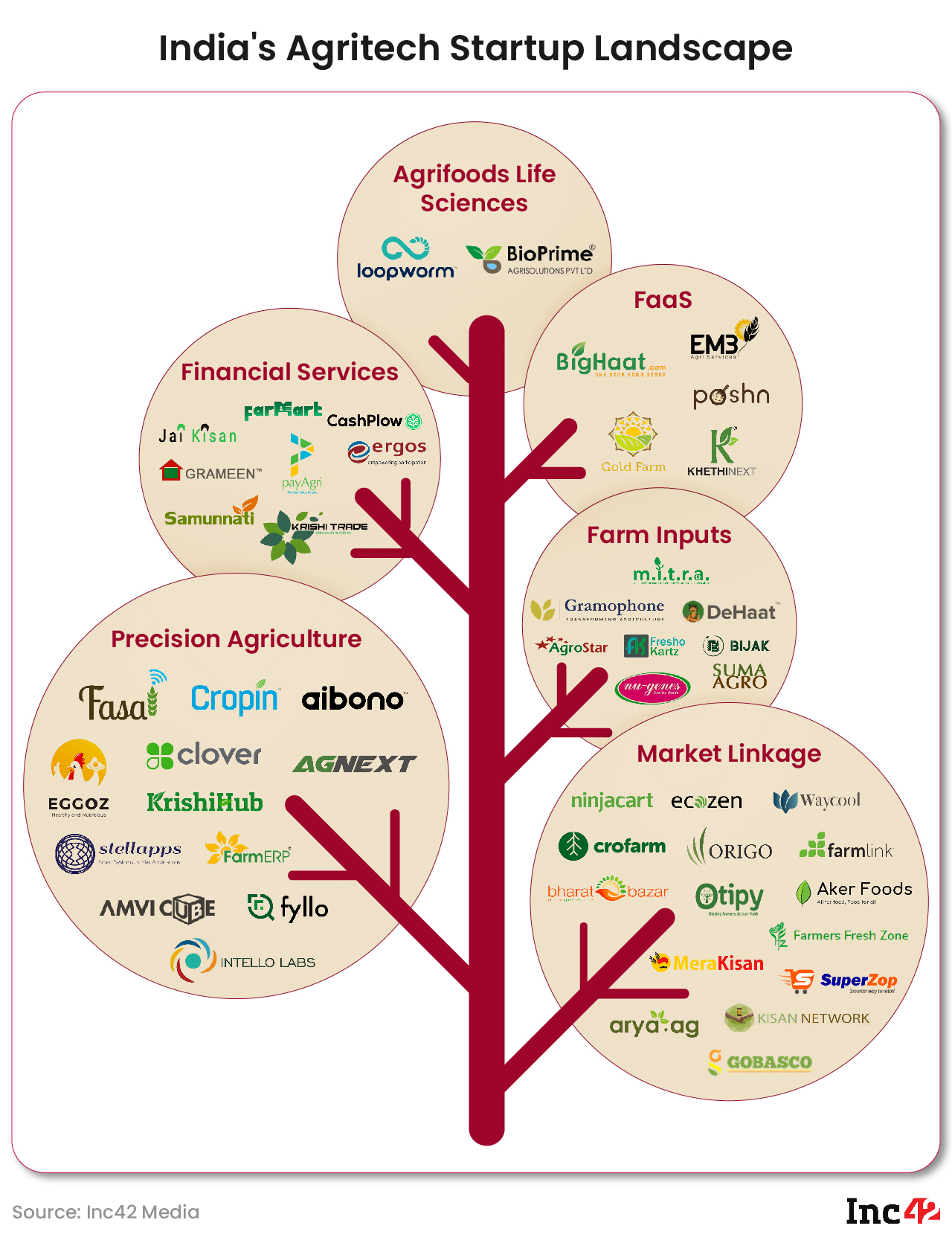

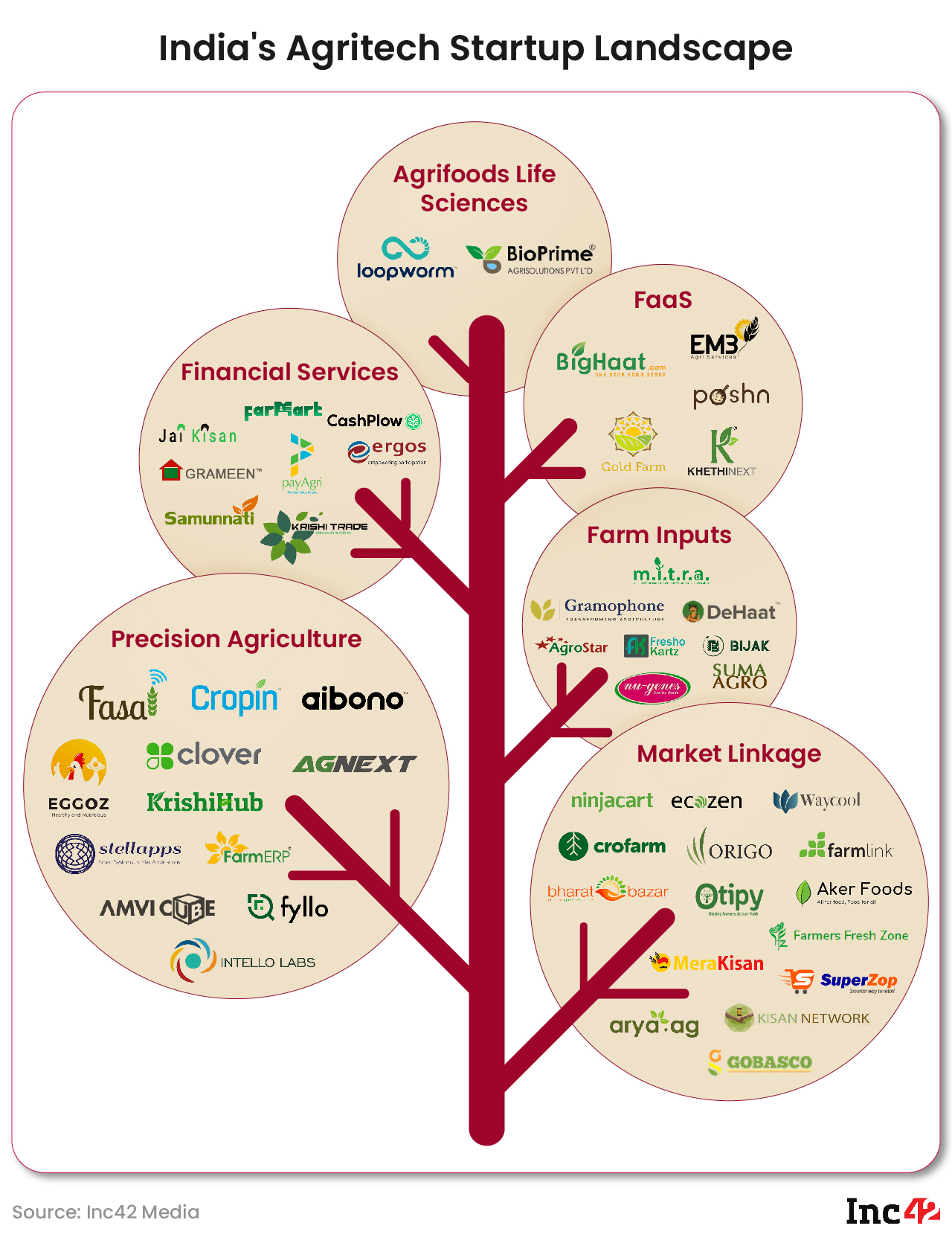

But Indian agritech startups are only still scratching the surface. One indicator is the lack of diversity in agritech business models among the existing startups despite the clearly large opportunities. Market linkage and supply chain startups dominate the landscape, while input marketplaces have also become a prominent agritech feature.

Before agritech startups, farmers did not have easy access to market linkage solutions, supply chain and warehousing tech, input marketplaces and price discovery tools. They were caught in a vicious loop of middlemen and were not able to dictate the terms when selling, often leading to major losses.

Kahn believes that’s why most agritech startups have looked to work in these areas to solve the major problems.

But his eyes are on the next generation of startups that are yet to come to the fore in India. Looking beyond market linkage startups and input marketplaces, Omnivore is doubling down on agrifood life sciences (AFLS) as a key sub-sector of agritech.

What Will Next-Gen Agritech Look Like?

While the global agrifood life sciences revolution has the US and China at its centre, Kahn believes India has the right entrepreneurial spirit and investor ecosystem to be a part of the AFLS boom.

Broadly speaking, AFLS includes four categories — agricultural biotechnology, novel farming systems, bioenergy and biomaterials, and innovative foods. Innovation in AFLS can also enable better climate resilience for crops and improve production without environmental damage. AFLS-focussed solutions will be the key to sustainable and profitable agriculture, which has remained a pipedream for Indian farmers so far.

Omnivore launched the OmniX Bio initiative to back early-stage agrifood life science startups and hopes that the VC ecosystem will follow suit. It is the largest fund of its kind in India — Omnivore has allocated roughly 15% of its $130 Mn corpus or $20 Mn towards OmniX Bio.

Its first investment was in BioPrime in December last year. Founded in 2016 by Amit Shinde, Renuka Diwan, and Shekhar Bhosale, BioPrime develops crop inputs that enhance farm yields without unintended environmental consequences.

Then in August this year, it backed Bengaluru-based Loopworm in a $3.4 Mn seed round. Founded in 2019 by Ankit Bagaria and Abhi Gawri, Loopworm enables optimised insect farming for small farmers while producing value-added nutrients and ingredients for B2B customers.

India’s Place In The Agritech Future

World-class life sciences talent from India continues to migrate abroad due to the larger opportunities that the US and Europe offer in this segment. But this global exposure has not yet trickled back to India. While we have seen engineers return from Silicon Valley to set up startups in India across most other sectors, this is not the case with food life sciences and agritech.

Laying the foundation for biotechnology and advanced life sciences in the education system can catalyse Indian agriculture and food production. But this will take years, Kahn contends. More Indians are doing cutting-edge life science research within 20 km of Boston, than in the entirety of the subcontinent, Kahn claimed.

Instead of waiting for the talent to come back, startups need to start doing the legwork in building the knowledge base themselves that next-gen companies in AFLS and agritech can leverage.

“This is exactly how the other sectors have grown. We always said India does not have the right talent, but we went ahead and built large unicorn startups despite that. We cannot just wait for the talent to emerge.“

Waiting For Agritech IPOs

While AFLS will be the future, the prospects of agritech startups in India today remain bright, with investors such as Omnivore also seeing potential upsides in the future in terms of exits.

Kahn believes that given the interest around the public listing of corporate agri giant Adani Wilmar in 2022 and Godrej Agro in 2017, even agritech startups have the chance to see bumper IPOs.

Most agritech business models in India are relatively simple to understand for an average retail investor, which is definitely an advantage in a volatile market.

That’s unlike a fintech stock such as Paytm, whose business model is not immediately clear to all investors, something even Paytm founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma pointed out earlier this year.

“There is tremendous retail investor demand for agribusiness. Every time an agribusiness goes public in India, it gets lapped up because as a percentage of the stock exchange, agriculture and agribusiness and agri processing and agri related equities are negligible.”

Of course, in the past six months, most IPOs have seen lukewarm subscriptions, particularly when it comes to new-age tech companies. But Kahn reckons that when these macroeconomic clouds clear, India is likely to see several agritech startups going public, just as in other sectors.

The contentious farm reform bills which have now been withdrawn turned the spotlight on the danger of Indian agriculture falling to large multinationals. But now the government’s eye has turned to agritech startups.

Earlier this month, the Indian government announced the setting up of an INR 500 Cr startup accelerator to back the scaling-up efforts of startups.

Kahn says the fear of MNCs taking over significant swathes of Indian agriculture is not unfounded. Existing agritech startups have managed to create significant value largely because Indian agriculture is still very democratic, unlike the West or China.

The Indian agribusiness ecosystem has a very nice even balance between multinationals, large domestic corporates and SMEs. “That is something India has done very well. In the West, everything is consolidated to just a handful of players, and there are monopolistic or oligopolistic tendencies in those markets.”

The competitive market allows startups to carve out niches across agritech segments even when corporate giants have a presence. While corporate giants are relying on massive distribution networks to gain the edge, startups have looked to add value by focussing on outcomes and solving decades-old challenges.

That’s why Omnivore continues to be bullish about agritech in general, but Kahn was quick to point out that agritech’s evolution towards AFLS needs to be accelerated or India will miss the bus.

“India can be a place where great companies are built. There’s a synthetic biology revolution that’s happening globally and we can’t just sit there and say, the system’s broken for another generation, while the Chinese and the Americans race ahead of us.”

Correction note (October 29, 18:00)

- An earlier version of this article had mistakenly mentioned that Godrej Agro had listed in 2022; The error has been rectified